![Mizuki_Shigeru_Kitsune_no_Yomeiri]()

Translated from Mizuki Shigeru’s Mujyara, Japanese Wikipedia, Showa: A History of Japan, Tales of Old Japan, Kaii Yokai Densho Database, and Other Sources

On a day when the sun shines bright and the rain falls, wise parents advise their children to play indoors. It isn’t that they are worried about them catching a cold. No, it is something more mysterious. For on such days the kitsune, the magical foxes of Japan, hold their wedding processions.

From Sakurai city in Ibaraki prefecture to Kashihara city in Nara prefecture, tales of Kitsune no Yomeiri appear all over Japan— with the sole exception of the northern island of Hokkaido. Most stories follow similar patterns with only slight variations. There are two phenomena referred to as Kitsune no Yomeiri—the bizarre weather called sunshowers where rain falls in broad daylight; and the procession of foxfire, called kitsune-bi (狐火), winding through the mountains late at night.

What does Kitsune no Yomeiri mean?

Kitsune no Yomeiri combines the kanji狐の (kitsune no; Fox’s) with嫁入り (Yomeiri; Wedding). In a literal translation, yomeiri means to “receive a bride,” as the custom is for the groom’s family to receive the bride on the wedding day as a proper member of their family. Until the middle-Showa period, Kitsune no Yomeiri Gyoretsu (狐の嫁入り行列; The Fox Wedding Bridal Procession) was more commonly used. But most drop Gyoretsu in the modern age. Just getting lazy, I suppose.

While Kitsune no Yomeiri is the most common term, there are regional versions of the same phenomenon. In Saitama and Ishikawa prefectures it is known as Kitsune no Yomitori (狐の嫁取り; The Taking of a Fox Bride). In Shizuoka it is called Kitsune no Shugen (狐の祝言; The Fox Wedding Celebration).

In Tokushima, the Kitsune no Yomeiri is a less happy occasion. It was called the Kitsune no Soshiki (狐の葬儀; Fox Funeral) and seeing one is considered an omen of death.

The Foxfire Lantern Procession

![Fox Wedding Painting]()

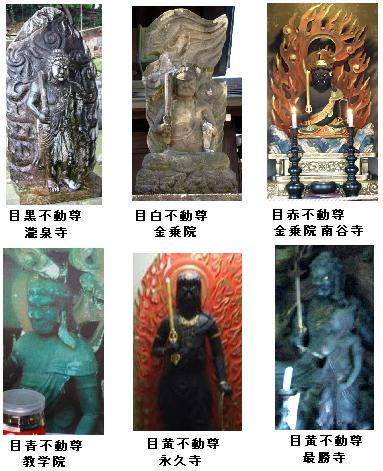

The Kitsune no Yomeiri has long been a part of Japanese folklore, although with the rise of the Inari Fox-cult during the Edo period it gained a greater significance and cultural permeation. A description of Kitsune no Yomeiri comes from the book Echigo Naruse (越後名寄; Encyclopedia of Echigo) published during the Horeki period (1751-1764).

“On dark and quiet nights, in secret places, strings of lanterns or torches can be seen stretching out single file in an unbroken chain more than two miles long. It is a rare site, but an unmistakable one. It can be seen most often in Kanbara county, and it is said that on such night young foxes claim their mates.”

The procession of lights became associated with weddings as it mirrored Japanese wedding ceremonies at the time. Based on traditions established during the Muromachi period (1392–1573), weddings were held at night and the bride was escorted over to her new home by a lamplight parade. This type of ceremony—called the Konrei Gyoretsu (婚礼行列; Wedding Procession) —lasted until the mid-Showa period when Western wedding ceremonies replaced traditional Japanese ceremonies.

Legends of the Kitsune no Yomeiri merged with existing stories of kitsune magic and bewitchment. People who tried to follow these foxfire lantern processions would find that they disappeared as soon as they got close—although on rare occasions traces of the ceremony were found. Shunjitsu Shrine in Saitama prefecture was said to be a popular place for fox weddings. Whenever a Kitsune no Yomeiri lit up the night, the mountain road leading to the shrine was covered with fox poop the following day.

![Fox Wedding Kimono]()

Stories of Kitsune no Yomeiri continued well into the Edo period. In Toshima village (modern day Kita-ku, Tokyo) Kitsune no Yomeiri was seen on several consecutive nights, eventually becoming one of the Seven Mysteries of Toshima. Mt. Kirin in Niigata prefecture is full of foxes, and Kitsune no Yomeiri was said to be a common occurrence. In both Niigata and Nara prefectures, Kitsune no Yomeiri was thought to be a good omen for the harvest, with the more lanterns being seen the more fruitful the harvest. A year with no fox weddings made people dread the upcoming famine.

The foxes of Gifu prefecture didn’t just content themselves with lanterns. The foxfire procession was accompanied by the sound of cracking and blazing bamboo, although when examined the following day the forests appeared untouched.

Scientific Explanation for Kitsune-bi

The procession of lamplights is not only a widespread phenomenon in Japan; it is worldwide. Japanese kitsune-bi is different from foxfire in Western legends, which comes from a phosphorescent fungus. It is more akin to the Will-o’-the-wisp, also known as ignis fatuus or “Fool’s Fire.”

The most common explanation is that these fires are the oxidation of the chemical phosphine caused by decaying organic matter, such as can be found in forests. Other suggestions are that they are a mere optical illusion caused by the setting sun. But there is no scientific evidence for either of these theories.

The foxfire procession kind of Kitsune no Yomeiri are rarely seen today. This is most likely due to the 1950s deforestation of Japan’s native forests and replanting with fast-growing industrial cedar. Whatever magic of the forests that produced the foxfire lights, it is now gone, sacrificed to industry.

Sunshowers and Fox Weddings

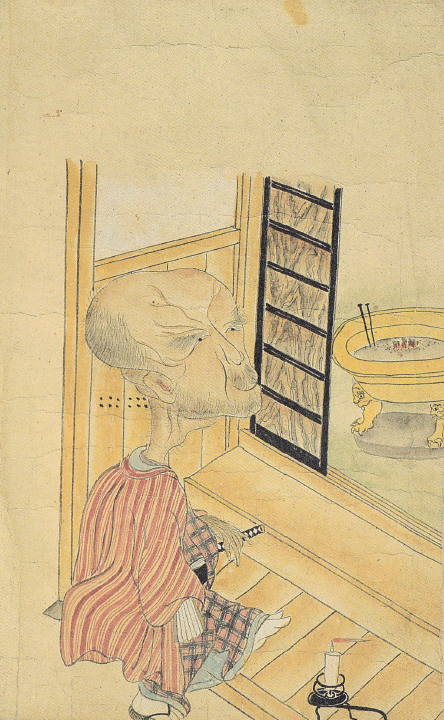

![Hokusai_Kitsune-no-yomeiri]()

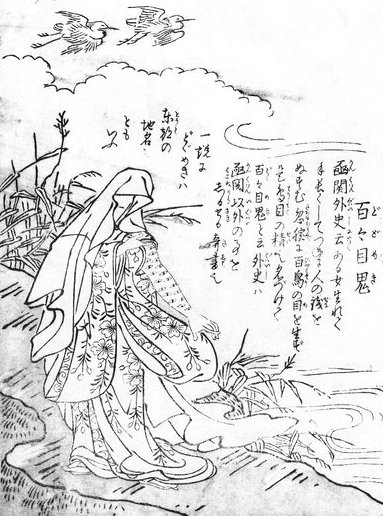

The Meiji period Tanka poet Masaoka Shiki wrote:

“When rain falls from a blue sky, in the Hour of the Horse, the Great Fox King takes his bride.”

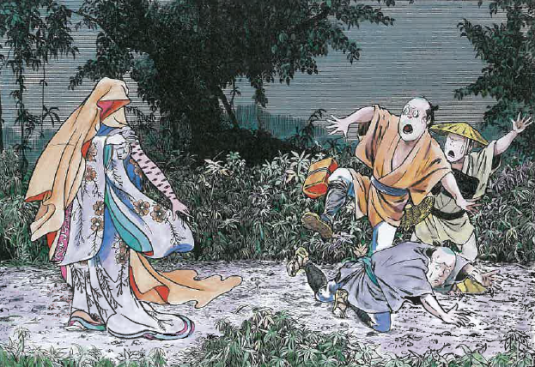

Another strange natural phenomenon goes by the name of Kitsune no Yomeiri, and in the modern era is much better known. On days when the sun shines and it still rains—a weather condition called tenkiame (天気雨) in Japanese or sunshowers in English—foxes are once again thought to hold their wedding ceremonies.

How sunshowers became associated with fox weddings is vague. Some say that it has to do with mountains where foxes are mostly found. There are times when mountains are covered in rain, while the town below is clear. People said that the foxes summoned the rain with their magic to hide their wedding ceremony. Others just think that because sunshowers are a mysterious occurrence, going against the natural pattern of clouds and rain, that people assumed a supernatural origin and associated it with foxes.

Although most pre-Meiji period accounts are of the foxfire processions, Katsushika Hokusai captured the sunshower-type in his painting Kitsune no Yomeiri-zu (狐の嫁入図; Picture of a Fox Wedding). The sunshower fox wedding was also mentioned in a 1732 Bunkraku puppet play Dan no Ura Kabuto Chronicles (壇浦兜軍記; The Chronicles of a Helmet of Dan no Ura).

As always, there are regional variations. In agricultural regions the sunshower version of Kitsune no Yomeiri was a good omen, promising rain for the crops and many children for the any new brides lucky enough to be married on such a day. In Tokushima, sunshowers are known as Kitsuneame (狐雨; fox rain) and not associated with weddings. In Kumamoto prefecture fox weddings are associated with rainbows, and in Aichi prefecture they are associated with hail.

How to See a Kitsune no Yomeiri

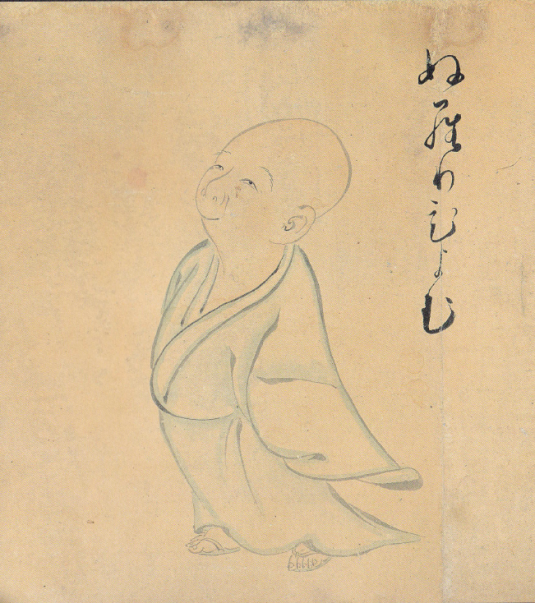

![Fox Wedding Ink Painting]()

While most people go out of their way to avoid seeing strange phenomena (getting wrapped up in kitsune magic is rarely healthy in Japanese folklore) there are a few rituals for the brave and the curious.

In the Fukushima Prefecture, a bizarre ritual exists of wearing a suribachi mortar on your head and sticking the wooden pestle in your belt, then standing under a date tree. Of course, this only works on the 10th day of the 10th month of the Lunar calendar.

Aichi prefecture has a much easier method—just spit in a well and weave your fingers together. You are said to be able to view the Kitsune no Yomeiri though the gaps in your fingers.

But most stories advise against seeing a fox wedding—foxes are powerful in Japanese folklore, but dangerous. A wise person keeps well away.

Kitsune no Yomeiri in Literature

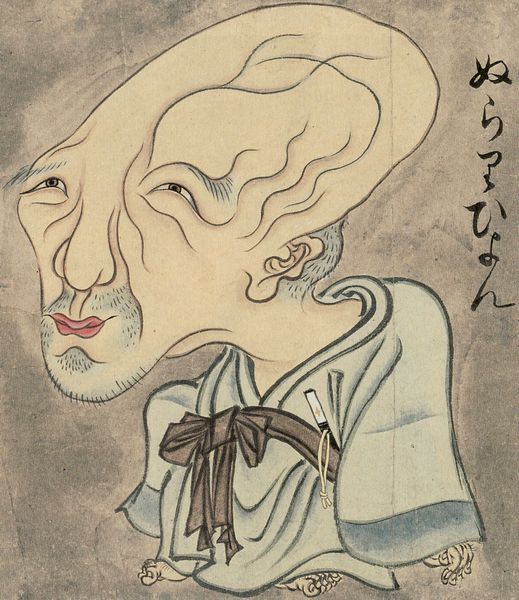

During the Edo period, numerous writers and kaidan-shu collections included first-hand accounts of Kitsune no Yomeiri, including those of people wandering into the middle of them and participating. The Kanei period (1624-1645) Konjyaku Kaidanshu (今昔妖談集; Kaidan Collection of Times Past), the Kansei period (1789-1801) Kaidanro no Tsue (怪談老の杖; A Cane for Old Kaidan Folk), and the Bunsei period (1818-1830) Edo Chirihiroi (江戸塵拾; Picked up Dust from the Edo Period) all contained first-hand accounts of encounters with Kitsune no Yomeiri.

![Kitsune no Yomeiri Ukiyoe]()

Some of the stories can be grim. A tale set in the Warring States period (1467-1568) tells of a young bride who suddenly fell sick and died. The night of her burial, a foxfire procession passed over her gravesite. Some are more uplifting, like the tale of an old couple who cared for a wounded fox pup, and many years later were honored guests at the fox’s wedding procession. Most stories, however, are of the voyeur nature—just a glimpse caught by a frightened soul hiding behind a tree when the wedding train passes by.

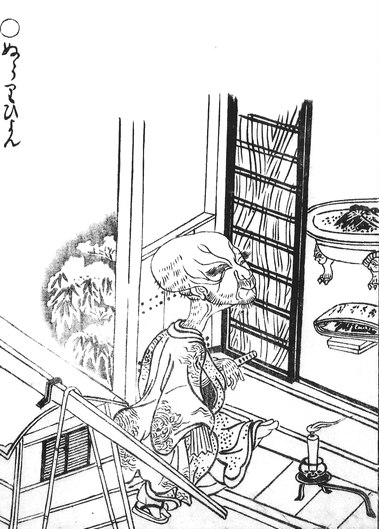

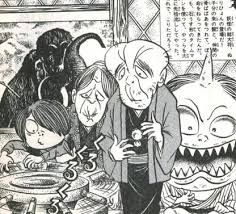

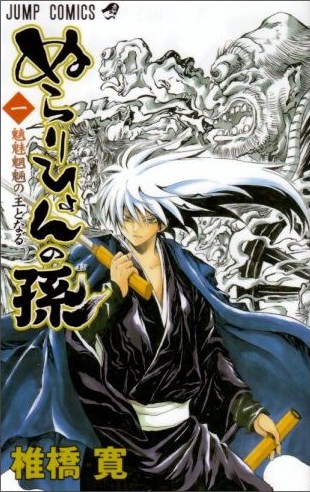

Mizuki Shigeru remembers being warned as a young boy against going outside during sunshowers. He writes about his memories of Kitsune no Yomeiri in his comics NonNonBa![]() and Showa 1926-1939: A History of Japan. Kurosawa Akira featured the sunshower-type Kitsune no Yomeiri in his film Dreams

and Showa 1926-1939: A History of Japan. Kurosawa Akira featured the sunshower-type Kitsune no Yomeiri in his film Dreams![]()

From Algernon Freeman-Mitford’s Tales of Old Japan, 1910

Algernon Freeman-Mitford describes the sunshower type of Kitsune no Yomeiri from the foxes’ point of view in his 1910 book Tales of Old Japan: Folklore, Fairy Tales, Ghost Stories and Legends of the Samurai![]() :

:

“Once upon a time there was a young white fox, whose name was Fukuyemon. When he had reached the fitting age, he shaved off his forelock and began to think of taking to himself a beautiful bride. The old fox, his father, resolved to give up his inheritance to his son, and retired into private life; so the young fox, in gratitude for this, laboured hard and earnestly to increase his patrimony.

![Fox_Wedding_Woodblock_Print]()

Now it happened that in a famous old family of foxes there was a beautiful young lady-fox, with such lovely fur that the fame of her jewel-like charms was spread far and wide. The young white fox, who had heard of this, was bent on making her his wife, and a meeting was arranged between them. There was not a fault to be found on either side; so the preliminaries were settled, and the wedding presents sent from the bridegroom to the bride’s house, with congratulatory speeches from the messenger, which were duly acknowledged by the person deputed to receive the gifts; the bearers, of course, received the customary fee in copper cash.

When the ceremonies had been concluded, an auspicious day was chosen for the bride to go to her husband’s house, and she was carried off in solemn procession during a shower of rain, the sun shining all the while. After the ceremonies of drinking wine had been gone through, the bride changed her dress, and the wedding was concluded, without let or hindrance, amid singing and dancing and merry-making.

The bride and bridegroom lived lovingly together, and a litter of little foxes were born to them, to the great joy of the old grandsire, who treated the little cubs as tenderly as if they had been butterflies or flowers. “They’re the very image of their old grandfather,” said he, as proud as possible. “As for medicine, bless them, they’re so healthy that they’ll never need a copper coin’s worth!”

As soon as they were old enough, they were carried off to the temple of Inari Sama, the patron saint of foxes, and the old grand-parents prayed that they might be delivered from dogs and all the other ills to which fox flesh is heir.

In this way the white fox by degrees waxed old and prosperous, and his children, year by year, became more and more numerous around him; so that, happy in his family and his business, every recurring spring brought him fresh cause for joy. “

Kitsune no Yomeiri Matsuri – Fox Wedding Festivals

![Fox Wedding Parade]()

Kitsune no Yomeiri remains a popular aspect of Japanese culture and folklore. Many towns hold Kitsune no Yomeiri festivals re-creating the famous processions. Most of these festivals are modern—coming from the 1950s to as recently as the 1990s—and were started as tourist attractions to draw people into town. Local politicians and businesses participate in the festival, and sometimes the fox bride and groom are selected as a sort of “beauty pageant.”

Not all are modern tourist traps, however. The Yokaichi city, Mie prefecture Kitsune no Yomeiri procession to Suzakiha Mamiyashimei Shrine dates back to the Edo period, and is a ritual to drive out evil spirits and ask for blessings for the harvest. The festival in Kudamatsu city, Yamaguchi prefecture, has also been held since ancient times, although it bears little relationship to popular images of the Kitsune no Yomeiri. It involves asking the blessing of a pair of white fox deities whose wedding ceremony is re-enacted every year.

Translator’s Note:

The latest entry in my series on yokai who appear in Mizuki Shigeru’s Showa 1926-1939: A History of Japan![]() . In the story, a young Mizuki Shigeru is told about foxes and Kitsune no Yomeiri by his friend and mentor, the local wise woman NonNonBa. Mizuki does not believe her until, later that night, he hears foxes barking from the mountain that NonNonBa talked about. It is at that moment he realizes all of NonNonBa’s stories—and the yokai themselves—are real.

. In the story, a young Mizuki Shigeru is told about foxes and Kitsune no Yomeiri by his friend and mentor, the local wise woman NonNonBa. Mizuki does not believe her until, later that night, he hears foxes barking from the mountain that NonNonBa talked about. It is at that moment he realizes all of NonNonBa’s stories—and the yokai themselves—are real.

Further Reading:

For more yokai from Mizuki Shigeru’s Showa: A History of Japan check out:

Hidarugami – The Hunger Gods

Sazae Oni – The Turban Shell Demon

Nezumi Otoko – Rat Man

For more kitsune stories, check out:

Tsukimono – The Possessing Thing

![]()

and

and

:

:

. In the story, a young Mizuki Shigeru is told about foxes and Kitsune no Yomeiri by his friend and mentor, the local wise woman NonNonBa. Mizuki does not believe her until, later that night, he hears foxes barking from the mountain that NonNonBa talked about. It is at that moment he realizes all of NonNonBa’s stories—and the yokai themselves—are real.

. In the story, a young Mizuki Shigeru is told about foxes and Kitsune no Yomeiri by his friend and mentor, the local wise woman NonNonBa. Mizuki does not believe her until, later that night, he hears foxes barking from the mountain that NonNonBa talked about. It is at that moment he realizes all of NonNonBa’s stories—and the yokai themselves—are real.

… sigh … thanks everyone for the preorder, and I apologize for the delays … ) check out some of the following!

… sigh … thanks everyone for the preorder, and I apologize for the delays … ) check out some of the following!